GUARDIAN

20 October 2014 by Maev Kennedy

Show features selection from Queen guitarist’s vast collection of images that appear three dimensional through special viewer

Brian May looks through an owl viewer in front of John Everett Millais’s Hearts are Trumps, which was inspired by Michael Burr stereoscopic photograph. Photograph: Ben Stansall/AFP

After badgers, foxes, and five-minute guitar solos, Brian May’s most passionate campaign has been to revive interest in the lost and almost forgotten art of Victorian stereo photographs. A selection from his vast collection has gone on display at Tate Britain, showing the photographs for the first time alongside the paintings that inspired them – and, in at least one case, a painting by a famous artist apparently inspired by a photograph taken by a now forgotten craftsman.

“It’s actually a shock to see them here – I never thought for one moment they’d agree to show them,” May said, gazing round the large gallery at the Tate that for the next six months will host a free exhibition of his photographs and the Victorian narrative paintings, which for decades fell equally out of fashion.

The photographers achieved a stereo effect by taking two photographs of the same scene, moving the camera slightly sideways for the second. Seen through the lenses of a special viewer, the two photographs mounted side by side combine into one apparently three-dimensional image.

“This is a very big thrill, being able to share my own excitement in these photographs. In the 19th century somebody called them ‘the poor man’s art gallery’ – but that was a derogatory term – they usually haven’t been taken seriously as art or photography.”

May has been collecting them since his first days on tour with Queen, when he used to buy stereo photographs for a few shillings from book stalls and junk shops. He now has more than 100,000 in his collection, many so rare that Denis Pellerin, an expert on the history of stereo photography and co-author of a newly published book on the subject with May, knows of no other surviving examples.

May rarely finds ones that are new to his collection now, but nervously revealed the highest price he has ever paid – £36,000, for an image capturing Queen Victoria’s daughter Vicky on her wedding day. “My heart was really pounding in the auction room,” he said.

He was surprised and touched that Penelope Curtis, the director of Tate Britain, came to the exhibition preview; she seemed equally struck at finding a rock star under her roof.

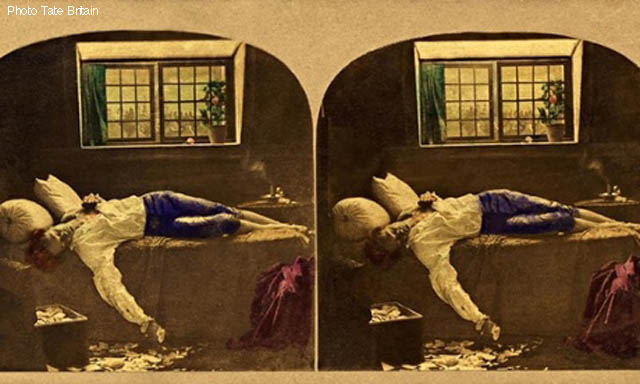

A detail from Michael Burr’s The Death of Chatterton c1861. Photograph: Tate Britain

Although May and Pellerin’s book is called The Poor Man’s Picture Gallery, the photographs were drawing-room entertainments for the middle classes, and not, at around a shilling and sixpence a packet – and much more for the frequently beautifully decorated viewers – for the real poor.

The photographers used great ingenuity in recreating some of the most popular paintings of their day, hiring actors, having costumes and props made and backdrops painted, and finally tinting the images by hand.

The only one sued for breach of copyright was James Robinson, over Henry Wallis’s romantic 1856 painting of the death of the teenage poet Thomas Chatterton. The painting was a sensation in its day, and is still one of the most popular in the Tate collection. In Dublin, where Robinson saw it, viewers were charged the enormous entrance fee of six shillings to see “this faultless and wonderful picture”. He published his own meticulously recreated version by 1856, with his young studio assistant posing as the dead poet, and was promptly sued not by the artist but by a man who had bought the rights to sell engravings.

Robinson lost and was forced to destroy his stock, and Pellerin knows of only two surviving examples, both in May’s collection – though two other photographers later recreated the picture again without being challenged.

The exhibition includes a huge painting by one of the most famous artists of the day, Hearts Are Trumps by Sir John Everett Millais. It depicts the three beautiful Armstrong sisters playing cards and almost drowning in a sea of silk frilled skirts. Although several Millais paintings inspired photographic versions, including The Order of Release showing a Highland rebel being freed to his family and rapturous dog, and My First Sermon, a little girl drowsing through a tedious church service, the title and the subject of Hearts Are Trumps seem to have come straight from a stereo photograph by Michael Burr, published six years earlier. Millais never acknowledged any link, but as May and Pellerin point out, painters rarely admitted using photographs as inspiration. Viewers can judge: the 1872 painting, and the 1866 photographs mounted in a stereo viewer, are both on display.

Tate curator Carol Jacobi said the photographs earned their place in the gallery. “These photographers were actually achieving remarkable things, achieving effects of lighting and composition, and capturing expression and movement which wouldn’t become common in photography until decades later. We think people will be fascinated by them.”

• Poor Man’s Picture Gallery: Victorian Art and Stereoscopic Photography is at Tate Britain until October 2015.

The Poor Man’s Picture Gallery, by Brian May and Denis Pellerin, is published by The London Stereoscopic Company