THE EXHIBITION IS STILL ON….!!!

BP Spotlight: ‘Poor man’s picture gallery’: Victorian Art and Stereoscopic Photography

Tate Britain: Display

7 October 2014 – 1 November 2015

ADMISSION FREE | Part of the series BP Spotlights

LINK TO TATE MODERN

Here are details of a related TV programme you may have missed…. and there’s a surprise or two!!

15 June – “Thomas Chatterton: The Myth of the Doomed Poet” BBC Four 8:30pm – 9pm

< VIDEO NO LONGER AVAILABLE >

PART TRANSCRIPT:

From approx 18:53 – 26:07 approx

MICHAEL SYMMONS ROBERTS: Shows like the colossal art treasures exhibition in Manchester in the summer of 1957, which ran for 141 days and attracted over a million visitors, provided the perfect showcase for “The Death of Thomas Chatterton”, as the painting had come to be known. Being toured round the country, the painting was disseminated to a far wider spectrum of society, including the new urban poor, than if it had remained in private ownership in London. And tapping into a growing Victorian fascination with death, Wallace’s painting proved a palpable hit. At a time of great and rapid urbanisation, the doomed and beautiful Chatterton represented a glimpse of something other.

This was the poet as dandy, yes, but more than that, this was the poet as counter cultural self-sacrificial, utterly intoxicating and dead. But even Wallace’s painting, like Chatterton himself, was to have a curious afterlife.

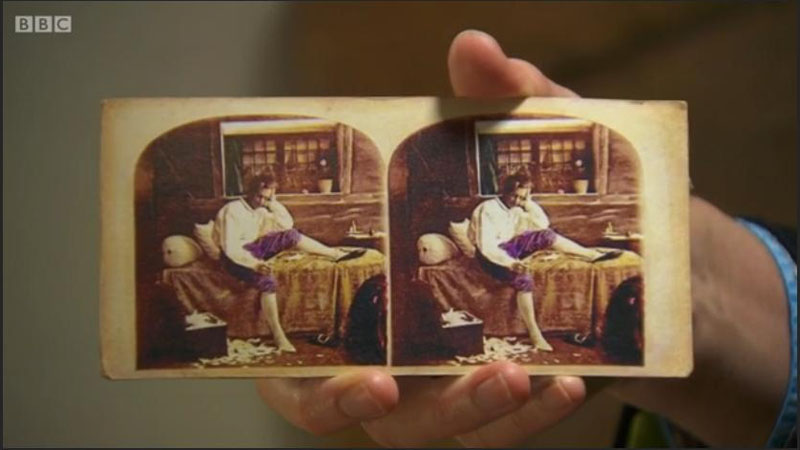

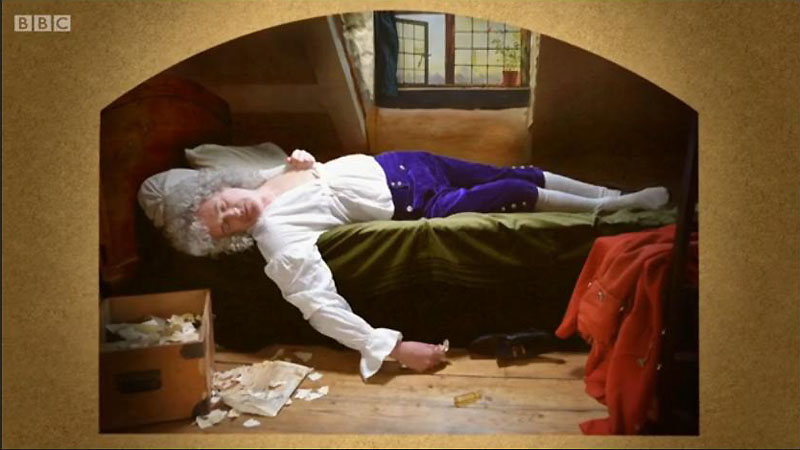

One of the many eager visitors who had queued to see Wallace’s painting on its tour was a dental surgeon, turned photographer, named James Robinson, and so moved was he that he decided to recreate the scene in the popular form of 3D stereoscopy – and now we can see it in an exhibition at Tate Britain. Displayed alongside Wallace’s painting for the very first time is Robinson’s remarkable take on the Chatterton myth.

At first glance it looks identical to Wallace’s painting with composition and colours, painstakingly copied, but look closer and you begin to notice differences. Chatterton’s face is not the same and the colours don’t look as vivid as they do in the oils, but in order to fully appreciate the stereoscopic image you need to view it as the Victorians did. It takes a moment for your eyes to adjust, but It’s extraordinary when they do. it’s like the hyper-real version of one of Wallace’s paintings, and your’e in the garret with Chatterton. It’s quite remarkable.

The driving force behind this exhibition comes as something of a surprise as it turns out to be none other than Queen guitarist, Brian May, who owns one of the world’s greatest collections of stereoscopic cards.

BRIAN MAY:

For me it goes back a very long way to my childhood when we used to get little stereo cards in Weetabix packets, and I remember the first time it fell out of the packet. What is this? – two little images that are very flat and quite boring but then you send off your one and sixpence for the viewer and you put the card in the viewer and suddenly this magic happens and you can feel like you can walk in there and it becomes a real-life experience, an immersive experience.

MSR: It it’s an odd effect. When I first looked through the viewer at “The Death of Chatterton” painting, which is a painting I know very well, it’s been so lovingly reproduced, there’s a strange hyper reality to it, which is a slightly odd thing with a death scene. Wonder how do you feel this relates to the painting, when you step into the stereoscopic world of Chatterton’s garret?

BM: Yeah, the painting is already immersive in it’s way, isn’t it. It’s designed to draw you in. You feel like you’re in that room with him. Of course, it lends itself perfectly to the stereoscopic medium and Robinson in 1859 obviously paid his six shillings to go and see the painting and thought, “Ah, I can do this at home and I can make stereoscopic version of this”.

It seems like it took in less than a week to do it and he had it advertised within a week.

If you put the original James Robinson stereo though, into a stereo viewer of the period, a Brewster viewer – this is how it’s done – you then open up the top to get some light in, and the view you get is quite stunning. Now this is a very old, faded and damaged card but the effect is still there. You still get this immersive experience. It still works.

MSR: It is like stepping into the room isn’t it, yeah.

BM: You get then the Victorian experience. But I have a very interesting thing here, which really nobody knows about. We discovered another version of the James Robinson view.

MSR: He’s alive.

BM: He’s alive. (laughs) But this is never ever seen. We now realised that there were two views, at least, of Chatterton – one with him alive, and one where he’s sadly passed away.

MSR: He’s, he’s alive but it looks like it’s about 30 seconds before the painting: his shoes off and he’s got all his torn up poems beneath. He’s not that cheery, is he?

BM: No, he’s got his poison ready.

MSR: He’s got his poison ready but isn’t it strange and ironic, this icon of the poetic death and it’s the one in the death that survived…

BM: The legend lives on.

MSR: The legend lives on. Do you find the painting and its stereoscopic image that striking? What draws you?

BM: I’m fascinated, yes. I think to all of us who’ve been involved in this, it becomes something that lives with you. It’s a kind of haunting experience. Chatterton was a kind of Victorian icon, I suppose, you know, representing the purity of the artist and the pain of the artist, and, yeah, I think we feel very drawn to it, in fact we’ve been trying to recreate it ourselves. As you have magnificently done it here. [chuckling] This is amazing .

MSR: Comparatively Pete Docherty on a Babyshambles album cover uses the image of “The Death of Chatterton” and I guess he has a similar image of a sort of popular bohemian figure. Do you think is stretching it too far to think of rock stars in a similar kind of vein to Chatterton?

BM: There is a parallel, isn’t there. It’s a kind of the tortured artist figure, I suppose, and you could think of Kurt Cobain. I think there’s a little truth in it actually. I think, you know, the artist frequently is this way because he is tortured and sometimes it leads to great creativity and success. Sometimes it leads the other direction down to despair and death, and I feel it’s still definitely, you know. I achieved success and fulfilled a lot of my dreams but I still very often get that feeling: Is it really worth anything, you know? What am I really doing? What’s my motivation? It runs through your life as an artist, this kind of self-questioning.

So in its extreme form maybe this is it. Maybe here’s he torn up poetry of the man who killed himself. It is a real story. It’s a fictional painting and it’s a fictional stereoscopic card, but it’s a real story. So maybe it’s the ultimate “Bohemian Rhapsody”.

(Laughing) Yeah, that’s completely ruined it for you, hasn’t it, yeah.

Michael Symmons Roberts’ documentary on the tragic poet, Thomas Chatterton, who also holds a fascination for Brian May of Queen – helping unravel the myth.

Poet Michael Symmons Roberts explores the mythic afterlife of the 18th-century poet Thomas Chatterton. With access to rare documents and artifacts, and featuring a surprising interview with Queen guitarist Brian May, Michael explains how Chatterton’s tragic early death in his London garret aged just 17 was immortalised by a succession of poets and painters and photographers – most notably by the pre-Raphaelite Henry Wallis in his masterpiece known as The Death of Chatterton – and how these successive images of the young Chatterton have saddled poets ever since with the notion of the doomed young artist suffering and ultimately dying in service to the muse.

SURPRISES… …

> > > > > > > > >

> > > > > > > > >

> > > > > > > >

> > > > > > >>

> > > > > > > >

> > > > > > > >

> > > > > > > >

> > > > > > > >

> > > > > > > > >

TATE EXHIBITION