“A poor little eclipse anorak”

**8 August 99**

Night & Day Magazine

Mail on Sunday

STARS IN HIS EYES

Queen Brian May is a self-confessed ‘eclipse anorak’ and still takes pleasure in using the telescope he built with his father.

If guitarist Brian May hadn’t chosen rock ‘n’ roll, he would have been an astonomer – and he can’t wait for the forthcoming total eclipse.

Interview by David Thomas

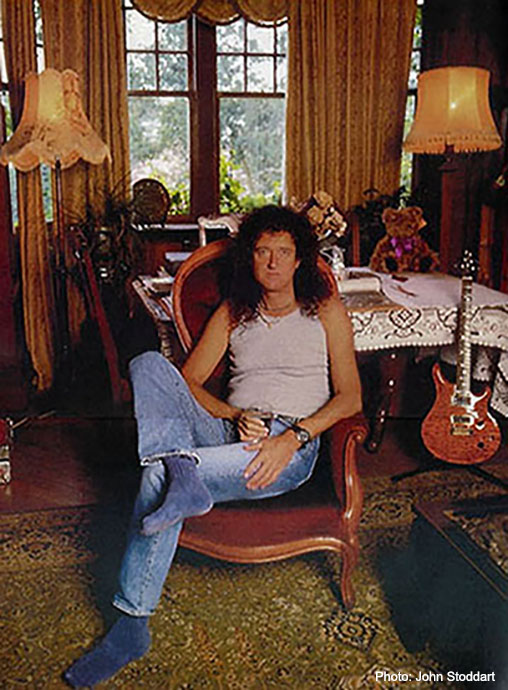

Photograph by John Stoddart

Brian May will be in Falmouth, Cornwall [August 1999], to see the eclipse on August 11. That’s a couple of hundred miles from his Surrey home, which some people might think was a fair way to go just to see the sun get briefly blotted out by the moon. But to May it’s no distance at all. The 52-yearold former Queen guitarist is, as he puts it, “a poor little eclipse anorak” and, as such, he’s criss-crossed the world on the trail of solar totalities.

It all began six or seven years ago. “I was working in California and I happened to see in the paper that an eclipse was coming up in Mexico. So I hopped on a plane, went down there and stayed in a little corrugated iron hut between two motorways, because everything else was booked up. It was crazy, like Cornwall will be. I sat there among loads of poisonous spiders and cockroaches and it just happened. I was quite surprised. There was the eclipse in the middle of a perfect blue sky. I took some pictures, which were lucky shots because I’ve never managed to get good pictures since then.”

It’s not for want of effort. May, usually accompanied by a computer expert called Tom Short, his closest friend at college, has gone comet spotting in the arid wastes of the Andes Mountains in Chile. He’s lain on a beach on the Caribbean Island of Curacao, checking out an eclipse as gentle waves lapped around his recumbent body. He’s had a deeply spiritual experience observing the sun’s disappearance from the ruins of an ancient Indian temple. He’s even been to Outer Mongolia.

“Tom and I combined it with a bit of tourism. We went to Beijing and then Ulan Bator, which is the capital of Mongolia. When else would you go to Ulan Bator? But we had a fantastic time there. On the day of the eclipse we woke at 2 am and travelled for six hours on the bus. When we got up, the weather was perfect and we could see the Hale-Bopp comet in the sky. But by the time we got to where we were meant to see the eclipse, we were in a total snowstorm. You could just about see the ghost of a crescent sun disappearing, but that was about it. Strangely enough, those are my fondest memories of eclipse chasing. It was just such a lot of fun, such another world.”

The magical power of an eclipse, so far as May is concerned, is that, “Suddenly, you can look at the sun and all its brilliance is blocked out. And you can see the sun’s atmosphere and its family of planets. For the first time in your life you can appreciate where we all sit in our tiny solar system. You can see Mercury and Venus very clearly and it suddenly all makes sense. I find that amazing. I almost get this feeling you could fall into the sun.”

May gets out his eclipse photographs and starts describing the phenomena that they depict. On the edge of the sun is a burst of orangey-red flame. “This is a little prominence,” he says. “Well, it looks little but it’s hundreds of times bigger than the size of the earth… it’s an eruption of hydrogen and it’s emitting H-alpha. This pink stuff [around the sun] is the chromosphere, which is, the slightly cooler layer which sits on top of the yellow photosphere, which you normally can’t see.”

If it sounds as though May knows what he is talking about, that’s because he does. He is that rarest of creatures, a rock star with a high-powered scientific pedigree. His passion for the stars was born as a boy, growing up in Feltham, Middlesex. A devoted fan of the comic-strip hero Dan Dare, he was allowed to stay up late to watch Patrick Moore’s TV programme The Sky at Night.

“I recently went on The Sky at Night, which was the fulfilment of a boyhood dream for me, because I watched every one of those when I was a kid and it made a huge impact, partly because of the awesome, splendid beauty of the images you saw, and partly because of Patrick Moore’s incredible enthusiasm. And there’s the programme’s theme music. He chose this piece of Sibelius which seemed to sum up the vastness and mystery of the universe. I was completely hooked. It was something I knew I was going to be captivated by all my life and that’s been true.”

——–

“Somewhere between music and

astronomy has always been where I am”.

——–

“Somewhere between astronomy and music has always been where I am. It’s a strange place to be but it makes perfect sense to me! There is a spiritual quality to the contemplation of astronomical phenomena, which is similar in my mind to the spiritual side of a piece of music that moves you.”

May’s childhood ambition was to become an astronomer. When he graduated from Imperial College, London, in 1966 with a First in Physics, the famous astronomer Sir Bernard Lovell invited him to carry out astronomical research at the Jodrell Bank observatory. May said no, partly because he had also been offered the chance to continue his studies at Imperial College, and partly because he wanted to be in London, where he could play music with his friends.

For four years he combined a PhD in the movement of interplanetary dust with an informal education in rock ‘n’ roll. After four years, his thesis was still not complete, his grant had run out, and he was making ends meet by teaching maths at a south London comprehensive.

In the end, he had to choose between rock and research, and rock won. As he admits, “I don’t think my discipline was good enough to be a good astronomer. Professional astronomers take their observing trips very seriously. But mostly what I wanted to do was go outside and look at the stars. Everybody thought I was a little bit weird, but I was more into the spectacle and the spirituality of it than taking measurements.”

May would use his travels around the world with Queen as a chance to meet astronomers. At airport bookstalls, while fellow band members Freddie Mercury, Roger Taylor, John Deacon and the band’s entourage were reaching for Melody Maker or Playboy, he’d be picking up Scientific American.

Looking back, it’s clear he found the craziness that accompanies rock stardom disturbing. “I know I’m a very lucky person. I’ve had the chance to fulfil so many dreams. And Queen was a wonderful vehicle. But I think it truly messed me up and I’m conscious that I have never really recovered. It’s like you never grow up. We’ve all suffered. Freddie, obviously, went completely AWOL. He wasn’t a bad person but he ws out of control for a while. But in a way, all of us were out of control. Perhaps I shouldn’t be speaking for Roger and John, but I think underneath it they’d agree with me – it screwed us up.”

One of the benefits of contemplating the vastness of the universe, though, is that it puts rock stardom – and everything else – into its true perspective. As May says: “It’s scary but it’s also comforting, I find. It makes all our problems seem so incredibly insignificant. There’s no reason to be depressed about anything because the worst that can happen to you is that you suffer and die – and how big an event can that he on a cosmological scale?”

May’s surroundings underline the idea that he isn’t too bothered by earthly concerns. He lives in a magnificent hilltop house in the heart of the Surrey stockbroker belt. Once inside, though, it doesn’t seem like the home of a man whose wealth has been estimated at £50 million – not one, at any rate, who feels the need for flashy displays of his fortune or fancy interior decoration.

A galleried hall at the heart of the building is undergoing a slow process of renovation. In the meantime, every available surface is littered with Star Wars toys – May, not surprisingly, is a massive fan of the science fiction movie series.

To one side of the hall is an airy kitchen that could belong in any large suburban home. To another is the dark, wood-panelled living room, furnished with Thirties-style settees upholstered in burgundy-coloured velvet. A collection of guitar amplifiers is piled at one end of the room. In a corner stands an old telescope. May made it with his father – just as they made the guitar which Brian played throughout his career with Queen – and he still takes pleasure from its use.

“We’ve been robbed of the wonder of the universe by modern lighting,” says May. “But it’s still not quite as enjoyable as chasing a really good eclipse.”