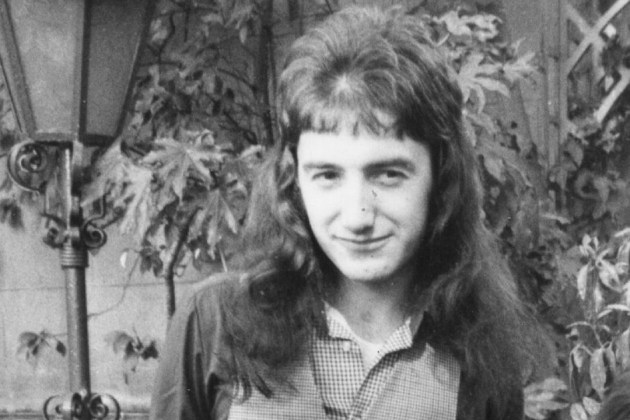

- John Deacon

QUEEN BEFORE QUEEN

THE 1960s RECORDINGS

PART 4: THE OPPOSITION

“We used to call him Easy Deacon”

JOHN DEACON WAS THE QUIETEST MEMBER OF A MIDLAND-BASED FIVE-PIECE WHOSE GREATEST AMBITION WAS TO PLAY ANOTHER GIG.

Initial research: John S Stuart, Additional research and text: Andy Davis

John Deacon was the fourth and final member to join Queen. He became part of that regal household 25 years ago this month, enrolling as the band’s permanent bassist in February 1971. His acceptance marked the culmination of a six-year ‘career’ in music, much of which he spent in an amateur, Leicestershire covers band called the Opposition.

From 1965 until 1969, Deacon and his schoolmates ploughed a humble, local furrow in and around their Midlands hometown, reflecting the decade’s mercurial mood swings with a series of names, images and styles of music. The most remarkable fact about the Opposition was just how unremarkable the group actPreually was.

Collectively, they were an unambitious crew, undertaking precisely no trips down to London to woo A&R men; winning only one notable support slot for the army of chart bands who visited Leicester in the 60s (opening for Reperata & the Delrons in Melton Mowbrary in 1968); and managing even to miss out on the option of sending a demo tape to any of the nation’s record labels. The band’s saving grace is its sole recorded legacy: a three-track acetate – although even this was done for purely private consumption, and has rarely been aired outside the confines of their inner circle.

It is perhaps indicative of the Opposition’s modest outlook that their most promising bid for stardom, a beat contest, was called off before they had the chance to play in the finals. For John Deacon and friends, its seems merely being in a band was reward enough.

Considering all of this, it’s easy to imagine the response to the following story, related in the 60s by one of the Opposition’s guitarists, Ronald Chester. “There was a teacher who worked at Beauchamp School, which John attended, who told fortunes. They went to see her one Saturday and were told, ‘John Deacon is going to be world-famous and very, very rich’. Of course, they all fell about laughing. she as determined that this was going to happen. But they all thought it was a joke.”

What particularly amused Deacon’s colleagues was the unlikeliness of this scenario, given the plain facts of his demeanour. John was born in Leicester in 1951, the product of affluent, middle-class, middle England. As a youngster, he was known to his friends as ‘Deaks’ and grew up to be quiet and reserved, what Mark Hodkinson referred to in ‘Queen – The Early Years’ as a ghost of a boy.”

“He is basically shy,” confirms Richard Young, the Opposition’s first guitarist/vocalist, and later keyboardist. “I suppose he was quieter than the rest of us – but he was quiet by nature. His sister, Julie, was the same. Once he got going, though, he wasn’t any different from anybody else. But on first approach, you really had to coax him out of his shell. We’d have to pick him up. He couldn’t walk down the road to meet us.”

CONFIDENT

Despite any lack of personal dynamics, Deacon was a capable teenager: “He was very confident,” recalls another of the band’s guitarists, David Williams. “But in a laid-back sort of way. He didn’t have a problem with anything. ‘Yeah, I can do that’, he’d say. We used to call him Easy Deacon, not because of any sexual preferences, but because he’d say something was easy without it sounding big-headed. I remember saying to him once, ‘I’m going to have to knock off the gigs a bit to revise for my ‘A’ levels. What about you? ‘No’ he said, ‘I don’t need to. I’ve never failed an exam yet and I’ve never revised for one.’ Ultimately, he was just confident, with a phenomenally logical mind. If he couldn’t remember something, he could work it out. And, of course, he got stunning results.”

John’s earliest interest was electronics, which he studied into adulthood. He also went fishing, trainspotting even, with his father. then music took over. After dispensing with a ‘Tommy Steele’ toy guitar, John used the proceeds from his paper round to buy his first proper instrument, an acoustic, when he was about twelve. An early musical collaborator was a schoolmate called Roger Ogden, who like Roger Taylor down in Cornwall, was nicknamed ‘Splodge’. But his best friend was the Opposition’s future drummer, Nigen Bullen.

I’d first got to know John at Langmore Junior School in Oadby, just outside Leicester, in either 1957 or 58,” recalls Nigel. “We were both the quiet ones. We started playing music together at Gartree High School, when we were about thirteen. We were inspired by the Beatles – they made everybody want to be in a group. John was originally going to be the band’s electrician, as he called it. He used to build his own radios, before we had any amps, and he fathomed a way of plugging his guitar into his reel-to-reel tape recorder. He was always the electrical boffin.”

The prime mover in the formation of the group was another Oadby boy they met on nearby Uplands Park, Richard Young. “Richard was at boarding school,” recalls Nigel Bullen. “He was always the kid with the expensive bike. He played guitar, and what’s more had a proper electric, with an amplifier. He instigated getting the band together. Initially, we rehearsed in my garage, and then anywhere we could. John played rhythm to begin with. He was a chord man, the John Lennon of the group, if you like.”

SWITCH

Despite his later switch to the bass, Deacon’s technique on the guitar also developed, as Dave Williams reveals: “Later on, I remember he could play ‘Classical Gas’ on an acoustic, which was a finger-picking exercise and no mean feat. It’s a bit like McArthur Park, a fantastic piece of music, and when I heard it, I thought, ‘Bloody hell. You dark horse!’ Because he never showed off.”

The Oppostition’s first bassist was another school friend of John’s called Clive Castledine. In fact, the group made its debut at a party at Castledine’s house on 25th September, 1965 (their first public performance took place the following month at Gartree’s school hall). Clive looked good and appreciated the kudos of being in a group, but he wasn’t up to even the Opposition’s schoolboy standards. “I was the least proficient, to put it mildly,” he admitted to Mark Hodkinson.

b>”His enthusiasm was 100%”, adds Richard Young, “but his actual playing ability was nil, so we had a meeting and got rid of him.” Deacon took over, initially playing on his regular guitar, using the bottom strings. “John was good.” Young continues. “It was no problem for him to switch to bass. He hit the right notes at the beginning of the bar, and we were a better band for it. Whereas Clive made us sound woolly, as anyone who just plonked away on any old note would. John was solid.”

DIARY

Young turned out to be the Opposition’s archivist, keeping a diary of each gig played, the equipment used, and the amounts of money earned (as indeed did John Deacon). Richard’s diary documented the day Deacon – now, of course, bassist in one of the world’s most famous groups – first picked up his chosen instrument. “In an entry for 2nd April 1966”, says Young, “it reads, ‘We threw Clive out on the Saturday afternoon. Had a practice in Deaks’ kitchen, and Deaks went on bass. Played much better.’ John didn’t have a bass so we went down to Cox’s music shop in King Sreet, Leicester, and bought him an EKO bass for £60. I paid for it, but I think he paid me back eventually!”

“John’s bass style with the Opposition was the same as with Queen.” reckons Nigel Bullen. “He never used to play with a plectrum, which was unusual, but with his fingers, which meant that his right hand is drooped over the top of the guitar. Also, he plays in an upward fashion, which I’d never seen before, certainly when we were in Leicester. Over the years, I’ve watched many bass players adopt that style. I’d say he has been copied a lot. I’ve mentioned this to him, but he doesn’t agree.”

Clive Castledine wasn’t the last member of the band to be dismissed. “The vocal and lead guitar side of the Opposition was changing all the while,” recalls Nigel. “Myself, John, and Richard Young were always there – as were Dave Williams and Ron Chester later on – but we had a succession of other musicians who I can hardly remember now. There was a guy called Richard Frew in the very early days, and a young lad called Carl, but he didn’t fit in. After we began playing proper gigs, Richard decided he wasn’t happy with his singing and wanted to move onto keyboards, so we brought in Pete Bart (formerly with another local band, the Rapids Rave) as a guitarist and vocalist. He was good, but again, didn’t last long.”

“Bart was a bit of a rocker, while we were all mods,” remarks Dave Williams.

“We were impressed by bands like The Small Faces and original Who but seemed to come from a different era altogether. “Deaks had the Parka and the fur collar,”remembers Ron Chester. “And short hair, a crew cut. Mirrors on his scooter.” Richard Young agrees: “John was more of a mod than us. But you couldn’t really pigeonhole the band, because our music went right across the board.”

Buying Deacon his bass was no one-off, and Richard Young is remembered as the group’s benefactor. Being older than the others he had a steady job working for his father’s electronics company in Leicester, which brought him a regular, and by all accounts, generous wage. He rarely thought twice before splashing out on equipment for the other members.

RECEIPTS

“Richard bought me a PA”, recalls David Williams. “But he didn’t ask, he used to think that the group needed it. He’d buy it and then say, ‘You owe me this’. My mum used to get really annoyed. She was at that going-through-my-pockets stage, probably looking for contraceptives. She once found a receipt from Moore and Stanworth’s, a local music shop. It was for a Beyer microphone, which cost about £30. I was still at school, getting pocket money, and my mum said, ‘What on earth is this?!’ Receipts on the Sunday dinner table, that sort of thing. It was good, though. the group needed it!”

“I was dead serious about the band,” claims Young, who switched to organ with the arrival of Williams in July 966. “Perhaps more so than anybody else, I could see it going nowhere if money wasn’t pumped into it.”

“Dick Young was an accomplished organ player,” adds Dave, “and he improved the group quite a lot. He always had plenty of dosh, and a car. But he was totally mad, a crazy bloke. He’d come round with an organ one week, then next week, he’d have a better one. He ended up with a Farfisa, with one keyboard on it, then one with two keyboards – one above the other. then he had a Hammond, an L 100, which ws really heavy. Then he had a ‘B’ series one. The ‘L’ was top-of-the-range and he sawed it in half to make it easier to carry!”

Dave Williams helped to improve the group as well. “He was at school with us,” says Nigel Bullen, “but in another band, who we always looked up to.” That band was the Leeds-based Outer Limits (who went on to issue several singles – without Dave – in the late 60s). “I joined the Opposition after they asked me to watch them and tell them what I thought,” recounts Dave. “The Outer Limits were older lads, all mods, but I was after something a bit more easy-going, and the Opposition were my own age. They were okay, but I first saw them at John’s house, when they were still practising in bedrooms, and they were absolutely awful. I said, ‘Have you thought of tuning up?’ They said they had. But it sounded like they were playing in different keys – totally horrendous. It was so funny. They were so conscientious, they’d all learned their bits, but hadn’t tuned up to each other. That was my first tip.”

“Our first proper gig was supporting a local band, the Rapids Rave, at Enderby Co-Op Hall,” recalls Nigel Bullen. “They used to play at this village hall every week, and then we ended up doing it every week for quite some time.” Richard’s diary records the Opposition’s debut taking place on 4th December 1965, and that the band’s fee was £2. Thereafter, they began to offer their services in the local ‘Oadby & Wigston Advertiser’, which led to bookings in youth clubs and village halls in local hot-spots like Kibworth, Houghton-on-the-Hill, Thurlaston and Great Glen.

SCHOOL WORK

By spring 1966, the Opposition were playing every weekend, school work permitting. The peaks and troughs of their career are illustrated by the following memorable gigs: one at St George’s Ballroom, Hinckley, on 23rd June 1967, when just two people turned up and the band went home after a couple of numbers; and a September appearance in a series of shows at US Airforce Bases in the Midlands, at which they were required to play for four-and-a-half hours with just two twenty-minute breaks. It was nothing if not diverse.

“It didn’t seem to matter what you played,” says Dave. “People would clap simply because you were making music. They never said, ‘Do you do Motown, or soul stuff?'” The band’s repertoire initially consisted of chart sounds and the poppier end of the R&B spectrum. “Although we were inspired by the Beatles, we never did any of their songs,” claims Nigel. “But we covered the Kinks, the Yardbirds, and things like Them’s ‘Gloria’, and the Zombies’ ‘She’s Not There’.”

They also altered their name slightly to the New Opposition, which they unveiled at th Enderby Co-Op Hall. “The name change was decided overnight when John moved from rhythm to bass guitar,” recounts Richard, whose diary records the date of the transition on 29th April 1966. Interestingly, though, it makes no mention of another local group also called the Opposition long thought to have been the reason for Deacon’s crew adopting the ‘New’. The change did act as an impetus for further development, however, instigated by Dave Williams, who soon took over as the group’s lead vocalist.

“When I joined they were doing all Beach Boys stuff,” he recalls, “and I think I may have brought in a little credibility. In the Outer Limits, I’d been playing John Mayall, the Yardbirds, that sort of thing, plus that group was into really good soul like the Impressions, and fantastic vocal bands from the States. So I had a broad musical knowledge by then, whereas the Opposition had been a bit poppy.” Appropriately, the words “Tamla” and “Soul” were now added to the Opposition’s ads and calling cards.

Towards the end of 1966, the New Opposition were enhanced further by the arrival of Ron Chester, who’d previously played with Dave Williams in the Outer Limits, as well as in an earlier band, the Deerstalkers. “Ron Chester was a bit eccentric,” claims Richard Young. “He never used to go anywhere without his deerstalker. He as a really good guitarist (“stunning” adds Dave Williams.) We were probably at our best when Ron was in the band.”

On 23rd October 1966, the New Opposition entered the local Midland Beat Contest. They won their heat, landing themselves a place in the semi-finals on 29th January 1967. They won this, too, and steeled themselves for the finals, which were due to be held on 3rd March 1967, when they were to be pitched against an act called Keny. The stars of the show would have been the nearest the Opposition came to having a rival: an outfit called Legay. (A year later, incidentally, this band issued a new collectable single, “No One [Fontana TF 904m £80].)

Unfortunately, for all concerned, however, the contest never took place. “That was a fiasco,” laughs Ron. “Somehow we won those heats, but in fact, I don’t remember seeing anybody else playing. I don’t know whether we won by default or not. After that, they pulled the plug on the competition – probably because they knew we’d be playing again!”

CASINO

“The heats took place in a club in Leicester called the Casino, which was the place to play,” adds Nigel. “The guy who ran the competition was an agent for the club. His company was called Penguin (or PS) Promotions and he walked like a penguin, too, with his feet sticking out. The final was going to be held in the De Montfort Hall, which is still the main venue in Leicester. We thought, ‘Crumbs, this is it, perhaps we might make the big time.’ But the guy did a runner with all the money – people had to pay to come to the heats. So the final was called off.”

David Williams wasn’t too fussed, as he scored another prize that night. “I remember taking a girl back to Dick’s car on the strength of us winning our heat. I said, ‘Can I borrow your keys, Dick?’ He said ‘What for? You can’t drive!'”

Were the New Opposition – or the Opposition, as they dropped the ‘New’ again in early 1967 – left in limbo by the cancellation of the Beat Contest? Having achieved the most public recognition of their talents so far, were they disappointed with the loss of the chance to prove themselves further?

“No. It was almost insignificant,” reckons Ron. “We didn’t really look upon it as a stairway to stardom.” And what would John Deacon have thought? “Nothing really, “suggests Chester. “It’s cancelled. What are we doing next, then?’ That would have been about the depth of it. We were a village band, all gathering at the church hall to try and improve our abilities. The financial aspect of it wasn’t in the forefront of our minds. We were more concerned with our music, and if we could get a booking doing it as well, to pay off some of the equipment, then that was a real bonus. Three bookings a week was enough for us while we were working or still at school.”

Despite any dodgy dealings, history does have the Penguin promoter to thank for the only professionally-taken photograph of the Opposition. (“We didn’t go much on photos in the band,” remembers Dave Williams,) On Tuesday 31st January 1967, two days after winning the semi-finals, the ‘Leicester Mercury’ dispatched a staff photographer over to Richard Young’s parents’ house in Oadby. Here, the group lined-up in the front room, looking more like refugees from 1964, rather than 1967. The only indications of the actual date are perhaps Ron Chester’s deerstalker hat and the ridiculous length of David Williams’s shirt collars – seven inches, no less, from neck to nipple.

“Dave was very extrovert,” recalls Nigel. “But we all had those silk shirts with the great long collars made by our mums and grandmas for our stage gear.” Dave admits: “Our clothes were all a bit mixed up. We had silk shirts with tweed jackets – which were fashionable for a while – and bell-bottoms. Musically, we were pretty good, better than most of the local bands around that time, but we had this squeaky-clean, schoolboy image which let us down. I used to get frustrated when we were billed with other bands, and they’d all play with so many wrong chords but had a better image and still the punters applauded. Were they stupid? We were still at school – we didn’t leave until we were eighteen – and weren’t allowed to grow our hair long.”

“After the mod thing,” he continues, “long hair became really important. Bands were growing their hair right down their backs. I remember getting to one gig with John and Nigel a year or so later, and the other group were already on. And when they saw us they turned round and said, ‘Look! They’ve got no hair!’ We were quite upset about that.”

“We also went through the flower-power look,” Dave adds. “And then we got into those little jumpers without any sleeves that Paul McCartney used to wear, the ones so small half your stomach showed. And then it was grandad shirts without the collars and flares.” Ron Chester: “The flowery shirts and flared trousers were everywhere. We looked like a right shower of poofters. But so did everybody else. You stood out if you didn’t wear then.”

1967 also heralded the arrival of an additional attraction to the Opposition’s stage show: two go-go dancers. At least, it did if the existing literature on the subject is to be believed. “I vaguely remember it,” admits Richard. “but speaking to Nig, neither of us can recall who those dancers were.”

Dave Williams throws some light on the subject: “They were the jet-set girls of the sixth form, they came from the big houses. They came to a couple of gigs and just started dancing. Somebody who booked us for the following week actually advertised us ‘with go-go girls’. But they were never really part of the show.”

ART

On 16th March 1968 for a gig at Gartree Schoo, the Opposition changed their name once again. “We called ourselves Art,” reveals Nigel, “because Dave was arty, that is, he was training as an artist. It was as simple as that.” Dave agrees: “It was my idea, because I’d been doing art at school.” Nigel Bullen was aware of another band using that name around the same time (the pre-Spooky Tooth outfit), but assuming them to be American, reckoned they’d be no confusion. As the Leicester-based Art never made it to London, there wasn’t.

Despite wording like “A time to touch and feel, to taste and experience, to hear and understand” appearing on the group’s tickets, Richard maintains that Art was “just the same band” as before. “Nothing changed.”

“It was mutton dressed up as lamb, really,” admits Ron Chester. “We thought if we were called something different, people might come because they were curious. But it didn’t make a lot of difference, the audiences were captive at the places we played anyway. There was nowhere else to go on a Friday or Saturday night. Everyone used to roll up to see whoever was on, whether they’d heard of them or not.”

1968 was the year psychedelia caught up with many provincial British bands. The Art were no different, but their acknowledgement of what had been last year’s scene in London was via sight rather than sound. Their light shows seem to have been particularly memorable, as Dave Williams explains: “They were brilliant. We used the projectors from school, filled medicine bottles with water and oil, and projected through them to get this lovely golden, amber backdrop. As the image came out upside down, when we poured in some Fairy Liquid, it dropped straight through in a blob, but came out on the wall like a giant green mushroom cloud. It was amazing, and we had about four of them at the back, projecting over the band.”

John Deacon was party to another of Dave’s exploits. “One day,” recalls Williams, “John and I bought a 100-watt PA – which was pretty big for those days – and took it into the lecture theatre full of kids at Beauchamp School (which Deacon had attended since September 1966) for our version of Arthur Brown’s ‘Fire’. We cranked it up as loud as we could, put the light show on, and let off these smoke bombs, which were DDT pellets we’d got from the chemist. All the kids started choking, and then the headmaster walked in with a load of governors. You could see the fury in his face. One of the governors asked what we were doing. ‘It’s a demonstration in sound and light, sir,’ I said. ‘We’re using these ink bottles turned upside down, but we’re a bit worried about these DDT pellets so we might knock the smoke on the head, but we’re still experimenting.’ And he fell for it!”

INFLUENTIAL

Towards the end of 1968, a crop of new groups began to have a profound effect on the maturing schoolboys: Jethro Tull, the Nice, Taste, and in particular Deep Purple. Ron: “We used to buy Purple records and learn to play them. We’d seen John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers and the Downliners’ Sect in Leicester, the Nice, King Crimson. These sort of groups. We learned a lot from just watching them. They were influential. There was always a big discussion in the band as to whether we should do a particular song. Once we’d decided that, they’d be another big discussion as to how we should do it. Everybody had their say.”

Hair, too, had finally began to grow: “John grew his quite long.” recalls Ron. “We all had longish hair, but not shoulder length. We couldn’t look too unkept fo the normal side of life, but we didn’t want to be too prissy for the other end of the spectrum. That was when we started playing universities, and we went a bit heavier. The audiences were far more serious minded about music and more enthusiastic. In some of the youth clubs we’d been playing, the audience would be moving around on roller skates, or peeling bananas all over the place, things like that.”

“We felt we were making an impression towards the last year or two of the band,” he continues. But it went no further. “We were at school, some of us had jobs, and there was an element of common sense overriding what we would have like to have done. None of us wanted to chuck in our apprenticeships or courses. If we’d had a flair for writing our own material, we might have taken off. But we just played what was popular, nothing different from most other groups. That wasn’t a basis on which to launch ourselves. So it never happened.”

“We didn’t think that far ahead,” admits Richard Young. “I just thought of playing and getting repeat bookings. John was probably the least ambitions of all of us, to be honest. I think he felt that there was no mileage in what we were doing, although it was good fun. I think he had the impression that this was a hobby, a phase he was going through.”

Sometime in the Sixties, possible 1969, but maybe earlier, Art recorded an acetate. Whatever the date, the crucial point is that John Deacon was present at the session. “We weren’t asked to do it,” recalls Nigel. “We just wanted to make a disc. I think it cost us about five shillings.”

The venue was Beck’s studio, thirty miles south east of Oadby in Wellingborough, Northamptonshire. “I’d never been in a studio before and it seemed awesome, really,” recalls Dave Williams. “It was a farily decent-sized room for acoustics. It was all nicely low-lit, with lots of screens. The guy knew what he was doing.” Richard Young was less impressed though: “I’ve been in studios all my life,” he says. “That was just another session. Nothing about it stood out.”

The “guy” Dave remembered was engineer Derek Tomkins, who informed the group that they could record three tracks in the time allotted. “We’d only gone in there with two, ‘Sunny’ and ‘Vehicle’,” says Nigel, “and we didn’t want to waste the opportunity, so Richard knocked up a little instrumental called ‘Transit 3’ – named after our new van, the third one – right there in the studio. Although we were purely a covers band, everybody had a bash at writing, but we never did anything of our own on stage. The exception was the ‘Transit 3’, which was incorporated into the set after this session.”

“‘Transit 3’ was about the only track we ever wrote,” reckons Richard Young (“Heart Full Of Soul”, as reported in ‘As It Began’, is in fact a Graham Gouldman number), “I initially had the idea, but I can’t really remember anything about it. It’s very basic. It wouldn’t take a great deal of effort to write something like that.” To the objective observer “Transit 3”, taped in mono but well recorded, is a fairly uncomplicated, organ-led scale hopper, reminiscent of Booker T & the MGs. “Everybody was listening to ‘Green Onions’,” confirms Nigel, “so Booker T would have been an influence there.” But for all that, it’s well played, with memorable lead and twangy, wah-wah guitar passages courtesy of Dave Williams. And, crucially, John Deacon’s thumping bass is plainly audible throughout. On this evidence, the Opposition were clearly a tight, confident outfit. “Tansit 3” could have been incorporated into any swinging 60s soundtrack, and no one would have jumped up shouting, “Amateurs”!

UNFAMILIAR

The other two tracks, covers of Buddy Hebb’s ‘Sunny’ and the more obscure, soul-tinged ‘Vehicle’ (later a hit for the Ides of March), featured a vocalist, but an unfamiliar one: another of the Opposition’s fleeting frontmen. “We had a singer for a while called Alan Brown,” recalls Nigel. “He came and went fairly quickly. He was good, really good. Too good for us, I think. That wasn’t him saying that. We just knew it.”

On both songs, Brown is in deep, soulful voice, sounding not unlike a cross between Tom Jones and the early Van Morrison – if such an amalgam can be imagined. The Art’s reading of “Vehicle” is edgy and robust, dominated by Richard Young’s distinctive keyboards with Nigel Bullen’s bustling drum work. Dave Williams is again in fine form, delivering more sparkling wah-wah guitar, while on the cassette copy taped from Nigel Bullen’s acetate, at least, John’s bass is very prominent, over-recorded in fact, booming in the mix.

“Sunny” goes one better, breaking into jazzy 3/4 time half-way through, before slotting back into the more traditional 4/4. It’s an imaginative arrangement, with alternate soloing from both Dave and Richard, while the whole track is underpinned by swirls of Hammond organ and John Deacon’s pounding bass.

“We did ‘Sunny’ as part of our stage set,” says Nigel, “but I don’t recall us ever going into the jazzy bit. That’s quite interesting. We might have talked about that before we went into the studio, but I think it was just for this session. Dave had two guitars, a six-string and a twelve-string, or it could even have been twin-necked. I still quite like the wah-way he played on that track. By this time Richard would have been onto his second or third organ – he was heavily intp Hammonds and Leslies.”

Operating as they did in a fairly ambition-free zone, and having prepared the listener for a mundane set of recordings with their trademark laid-back approach, Art’s acetate comes as something of a revelation. Let any bunch of today’s schoolboys loose in a studio for an afternoon and defy them to come up with something half as good!

Just two copies of the Art disc are known to have survived. John Deacon’s mother is believed to own one and Nigel Bullen has the other. “I’d forgotten all about this record,” admits Nigel. “We know that one copy was converted to an ashtray! We stubbed out cigarettes on Richard’s at rehearsal one night.” Although treated with anything but respect at the time, the importance of the disc is now apparent to Nigel Bullen: “This is probably John Deacon’s first recording, apart from tracks he did in his bedroom on his reel-to-reel, which are probably long gone. Although, knowing John, they’re probably not!”

The beginning of the end for Art came in June 1969, when John Deacon left Beauchamp. With a college course lined up in London, his days with the band were obviously numbered. He played his final gig with the group on 29th August at a familiar venue, Great Glen Youth Club. By October, he’d moved to London to study electronics at Chelsea College of Technology, part of the University of London.

Another blow was dealt in November, when the band’s lynchpin, Richard Young, left to join popular loacl musician Steve Fearn in Fearn’s Brass Foundry. “They were a Blood, Sweat and Tears-type of group,” recalls Richard, “and paid better money than I’d been used to. I was out five nights a week on about Ł3 per night, against an average of about Ł10 between us.” The previous year, Richard had played session keyboards on the Foundry’s two Decca singles: “Don’t Change It” (F 12721, January 1968, Ł10) and “Now I Taste The Tears” (F 12835, September 1968, Ł8.)

SAVAGE

Ron Chester departed shortly afterwards and gave up music: “I left in the early 70s, after John Deacon moved to London. John was replaced by a bass player who was called John Savage, who unsettled me. He had different tastes and drove us a bit hard. His approach was totally different to Deaks’s, and he was much more interested in the financial side of things. We’d all been mates before, we didn’t just knock about for the band. It just wasn’t the same.”

Nigel, Richard and Dave pushed on into 1970 with the new bassist, changing the band’s name again, this time to Silky Way. They returned to Beck’s studio to record a cover of Free’s “Loosen Up” with anohter vocalist, Bill Gardener, but that was the band’s last effort. Dave left after falling into Nigel’s drumkit, drunk on stage at a private party one Christmas. “I waited for them to pick me up the next day,” he recalls sheepishly, “but they never came.”

Richard and Nigel moved into a dinner-dance type outfit called the Lady Jane Trio – “Corny, or what!”, laughs Bullen – but Nigel left music altogether soon afterwards to concentrate on his college work. Richard turned professional, moving into cabaret with the Steve Frearn-less Brass Foundry, before forming a trio called Rio, finding regular work on the holiday camp and overseas cruise circuit. In the late 70s, he joined a touring version of the Love Affair.

Down in London, John Deacon caught a glimpse of his future world-beating musical partners as early as October 1970, when he saw the newly-formed Queen perform the College of Estate Management in Kensington. “They were all dressed in black, and the lights were very dim to,” he told Jim Jenkins and Jacky Gunn in ‘As It Began’. “All I could really see were four shadowy figues. They didn’t make a lasting impression on me at the time.”

While renting rooms in Queensgate, John formed a loose R&B quartet with a flatmate, guitarist Peter Stoddart, one Don Carter on drums and another guitarist remembered only as Albert. The new band was hardly a great leap forward from Art: they wrote no originals, and when asked to perform their only gig at Chelsea College on 21st November 1970, they hastily billed themselves – in a rare fit of self-publicity for the quiet Oadby boy – as Deacon.

A few months later in early 1971, John was introduced to Brian May and Roger Taylor by a mutual friend, Christine Farnell, at a disco at Maria Assumpta Teacher Training College. They were looking for a bassist, John auditioned at Imperial College shortly afterwards. Roger Taylor recalled Queen’s initial reaction to Deacon in ‘As It Began’: “We thought he was great. We were so used to each other, and so over the top we thought that because he was quiet he would fit in with us without too much upheaval. He was a great bass player, too – and the fact that he was a wizard with electronics was definitely a deciding factor!”

How did the members of the Art/Opposition back in Leicester, view John’s success with Queen? “It wasn’t sudden,” says Ron Chester. “First we heard he’d got into another group. We couldn’t believe that – were they deaf? There were all these sort of jokes going along. Then we heard he’d got a recording contract and the next thing he had a record out. It was a gradual progression. No one dreamed he would end up the way he did.”

“I don’t think we expected success for any of us”, admits Nigel Bullen. “Richard maybe. He was the first one to go professional. But when John left for London to go to college, he left all his kit here. I thought that was the end of it for him. He had absolutely no intention of continuing. His college course was No 1. It was only after he kept seeing adverts for bass players in the ‘Melody Maker’ that he became interested again.”

He also seemed to lose some of that ‘Easy Deacon’ touch which so impressed Dave Williams in the 60s. “He’d ring up these bands,” continues Nigel, “but when he found out they were a name act, he’d bottle out. When he went to auditions for anonymous bands, where he would queue up with about thirty other bass players, he had a bit of confidence. He just wanted to play in a decent band. Once I heard what Queen had recorded at De Lane Lea, and John played me the demo of their first album, I thought they were well set.”

CABARET

By early 1973, Dave Williams had forsaken a career in animation to join Highly Likely, a cabaret outfit put together by Mike Hugg and producer Dave Hadfield on the back of their minor hit, “Whatever Happened To You (the Likely Lads theme)”. While Dave was in the band, they recorded a follow-up single which wasn’t realsed, before evolving into a glam rock outfit, Razzle, which later became the Ritz, who issued a few singles. “During Queen’s early days, before they’d had any real success, John came to see us once,” recalls Dave, “and said, ‘I wish I was in a band like this which would actually play some gigs’.”

Dave concludes: “I remember John coming round once around that time, saying ‘I’ve got a demo’. ‘So have I!’, I said. So we put his on first, and the first track was ‘Keep Yourself Alive’. My mouth dropped wide open and I thought, ‘Bloody hell! What a great track’. I remember saying that the guitarist was as good as Ritchie Blackmore – who was still our hero then – and thinking ‘they’re serious about this. This is the real thing’.”

Thanks to Nigel Bullen, Richard Young, Ron Chester and Dave Williams for their time and illustrations. Thanks also to Mark Hodkinson.