“A Village Lost And Found” by Brian May and Elena Vidal

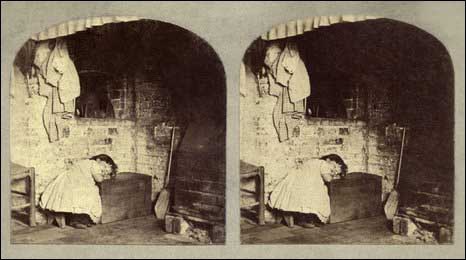

If you relax your eyes and look “through” this image – you may be able to see it in 3D (but stop if it feels uncomfortable)

BBC NEWS

21 Oct 2009

By Tim Masters, Entertainment correspondent, BBC News – here

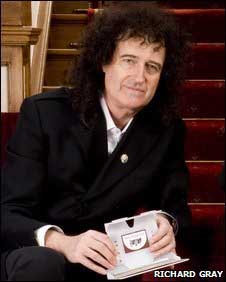

Rock guitarist Brian May is best known for his work with Queen and his PhD in astrophysics.

But what is less well known is his lifelong passion for 3D photography.

While he was touring the world with Queen, May was collecting thousands of stereoscopic photographs and the viewers that bring them to life.

It was in this way that he discovered the work of Thomas Richard Williams, who in the 1850s created a series of 59 stereo cards depicting life in a small English village – Hinton Waldrist in Oxfordshire.

May has teamed up with photographic historian Elena Vidal to produce a book of Williams’s stereoscopic 3D images, A Village Lost and Found.

Here May discusses the roots of his love of stereo photography, his dislike of the paparazzi, and what he thinks about the future of 3D cinema.

So this all began with a packet of Weetabix?

There was always something in cereal packets in the old days, puzzles and stuff. Anyway, these little 3D views came along and you could send off for a viewer for two and sixpence and a couple of packet tops. So I did, and it was magic to me that these little pairs of flat-looking pictures suddenly turned into something completely real. It was a window onto a world that I’d never seen before.

When did you first come across postcards by TR Williams?

It must have been the late 60s. I was going to Christie’s near my college, but I couldn’t afford anything because I was a destitute student.

Very early on in my life I learned to “free-view”, so I could see stereo without the viewer, which is a handy skill to have.

Is that like those Magic Eye pictures from a few years ago?

Yes, I used to set my eyes in that position and flick through all the cards in the boxes in Christie’s – and one of these things would suddenly leap out; because of course when you’re in the free-viewing mode, you see everything in stereo immediately.

So you collected these all the time you were with Queen?

Yes, all those years on tour I was able to interact with photo dealers all around the world. Normally, I would invite them to the gig, and they would be quite surprised, because that wasn’t their world.

Then I’d say, ‘okay, what have you got for me?’, and they’d get out a couple of boxes of these little stereo cards and that would be my treat for the night, my reward for playing the gig!

So all this was going on behind the rock star lifestyle…

I began collecting everything stereoscopic. It’s a large subject, I have literally tens of thousands of them, but obviously a very small number of those are by TR Williams. But the whole period of the early 1850s up to about 1858 is absolutely magic from the point of view of stereo.

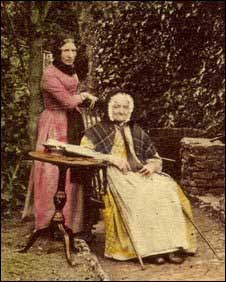

What’s your favourite image from the book? I like the one of the village school mistress…

Me too, it’s one of the first ones I saw. There are so many levels to this series, that’s why it’s been an endless fascination to me. There is the picture that you first see, then you see its wonderful stereo composition and you feel like you can walk in. Then you turn the thing over and very often there’s a verse on the back, which gives everything yet another dimension.

Any other favourites?

I love Little Polly Gone Fast Asleep [see top image] – it’s the only one of the series taken indoors. If you go to these little thatched cottages you realise how difficult that would have been because the windows are so tiny.

And Tummus Standing For His Picture – the verse on the back speaks about how intimidating he finds the camera – almost as if it was a gun pointed towards him.

I really identified with that. Even though I love photography that’s how I feel when some paparazzi points their camera in my face. I feel threatened and intimidated.

Do you ever get used to the paparazzi?

You think you get used to it and then you get caught in a moment when you’re harassed and someone is suddenly sticking something in your face and capturing something that can be used against you. You can find a story in the paper that paints you as something completely different from what you are.

In the age of mobile phones, do you get snapped by people when you’re out and about?

Yes. The whole world is a paparazzo now – if I’m out in the high street all kinds of people will be trying to message on their mobile phones, but you know its directed towards you – because it flashes! And the next minute it’ll be on the internet.

Back to 3D photography, it’s going through a real golden age at the moment.

I do enjoy seeing 3D films. I’m glad there’s this great renaissance – with 3D television coming too. By pure coincidence we seem to have timed the book incredibly well.

Do you think 3D in film and TV is a bit of a gimmick?

Hard to say. If you look at the history of stereoscopy it’s always arrived in a great flurry of excitement and then disappeared a few years later.

I certainly hope it will be around for a long time to come. Having been an evangelist for some 30 years and have people look at me weirdly, it’s quite strange to have it all around now. You feel almost redundant.

A Village Lost and Found, by Brian May and Elena Vidal, is published this week by Frances Lincoln.

Find out more on BBC Radio 4’s Open Country on Saturday 31 October at 0607 BST, repeated on Thursday 5 November at 1500 BST.